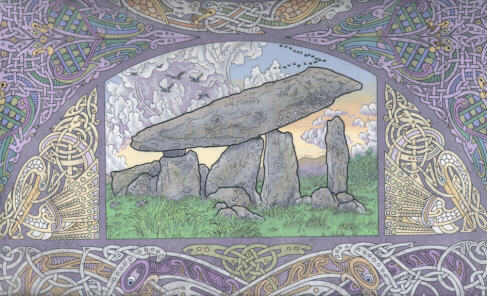

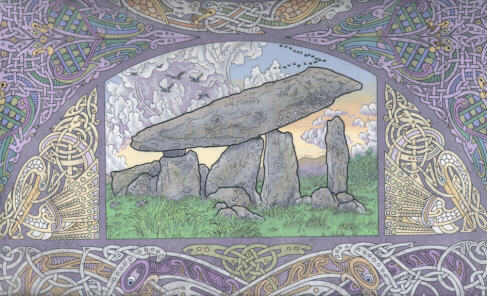

Detail from The Gateway

The Celtic Art of Jeff Fitzpatrick

Article by Stephen Walker

Published in Dalriada Magazine, Volume 14 Number 3, Lughnassadh 1999

Detail from The Gateway

What is new and what is copied from the past? In the present revival of Celtic art, the question is rarely asked. George Bain, when he wrote Celtic Art; the Methods of Construction, urged that his teaching be used to create new visions and applications using the visual language of interlace, spirals and key patterns. Yet Bain himself often mined the repertoire of ancient designs from manuscripts like the Book of Kells or historical monuments and artifacts as a pattern book for his creations.

For the most part it is assumed that today’s Celtic artists and designers are using traditional sources. Despite Bain’s intention that his book be used to teach the method and vocabulary of Celtic art for inventive new creations, sadly it is used more often as a source of clip-art. So prevalent is the attitude that Celtic design must be copied from an historical source to be authentic, that even genuinely original creations cloak themselves with statements such as "inspired by the Book of Kells."

There is clearly something ancient about Jeff Fitzpatrick, a young artist working on the West Coast of Ireland. Yet his art is fresh and vibrant. To put his work in a historical perspective Jeff explains, "The monks who created the Book of Kells were totally focused on pleasing God. So their work was for God’s eyes only and not for the ordinary person. They believed that the ordinary person could not possibly relate to or understand the minute work. It is often repeated that the resulting creations were the work of angels rather than the work of men."

The difference between Jeff and the early Christian monks is that he acknowledges the divine but is guided towards creating pieces upon a scale for today’s people to understand and be inspired by, blending the spiritual, mental & physical. Many of Jeff’s designs are learned and practiced like songs. What began as an adaptation from a derivative source has been practiced over and over again. These designs redrawn and mastered through disciplined study and practice, have evolved from a constant revaluation and refinement of interlaced bird and animal forms to fit new spaces and new color schemes. New arrangements are thus sung to old melodies and new expression given to ancient tunes.

As a child growing up in Belfast, Jeff began drawing cartoon characters from picture books. By the time he was age nine he was attempting interlaced serpents and soon was introduced to the Book of Kells. By age thirteen Jeff had discovered the work of Ireland’s leading Celtic artist, Jim Fitzpatrick (not a relative). The mythological subjects decorated with Celtic borders were a fascination not only for their quality and content, but also because Jim Fitzpatrick was a living artist. To young Jeff this meant that Celtic art was not just something from the past, but something alive giving hope that he could be part of an exciting new manifestation of Celtic art in his own lifetime. Jeff wrote to Jim Fitzpatrick in Dublin and sent him a drawing. Jim Fitzpatrick responded positively and Jeff cycled from Belfast to Dublin to meet him. Soon Jeff was drawing zoomorphic boarders and assisting Jim in the creation of his work.

His association with Jim Fitzpatrick also gave Jeff the opportunity to meet other Celtic artists. Courtney Davis and Aiden Meehan were friends of Jim Fitzpatrick and would occasionally get together and share ideas. As time passed Jeff worked with several other artists and craftsmen. He spent some time apprenticed to a tattoo artist. He worked up designs for a monument carver. Most recently he has been designing wood carvings in County Meath with carver Claidhbh O’Gibne.

Recent works

Jeff’s current body of work consists of ink drawings painted with acrylics on acetate film. He has been working on a series of four allegorical figures called "The Irish Treasure" that each center on a female allegorical figure. In his own words he describes the first piece completed of the series:

"The Irish Treasure relates to the Holy Grail. Symbolizing the journey of the physical self coming together with the Spiritual self and realizing Heaven on Earth. The Grail itself as the pure essence of Heaven is presented through the divine feminine, which is the spiritual essence of Er�u (Ireland). I have always related the divine feminine in Ireland with the Bean-sidhe, women of the Sidhe. These women are always royally attired and full of magical power. The realization of the true meaning of the Grail will bring you closer to the divine feminine and the divine masculine and the source of all Creation."

Other recent works are "The Gateway" centering on an image of a dolmen, "The Hunting Page" relating to the Irish Creation Myth and a series of highly embellished crosses.

Zoomorphic Symbolism

Zoomorphic designs dominate the Celtic ornamental decoration of Jeff’s work. The interlaced animal, bird and human forms that are so characteristic of the Book of Lindisfarne fill much of the space in his compositions. If you research the meaning, the kind of literary sources that academics rely on simply do not exist; however, it would be unthinkable that no symbolic significance was intended. Due to the lack of historical literary references, the true meaning of the ancient symbolism can never be proved. Scholars are very uneasy about discussing symbolic significance of interlaced ornament. Jeff does not simply use the menagerie of Celtic beasts haphazardly. Study of Irish myth as well as 20th century "Celtic Twighlight" mysticism has given Jeff ideas about what the ancient scribes had in mind for their fantastic creations. Just as importantly these ideas guide him in using the symbols in a personally meaningful way in his own work.

The most prevalent animals involved in zoomorphic patterns are birds, dogs, and serpents. Birds are messengers between the physical and the other, non-physical word. Many of the birds are recognizable as herons . Birds usually placed on the boarders guide the eye to the center.

Dogs symbolize guardians between this world and the next and were referred to in Irish tradition as being white with red ears. The dog, when placed on a particular piece was normally guarding the center. Usually four dogs symbolize the four sacred directions. Serpents, symbolize old wisdom of Ireland, Celtic and pre-Celtic. When St. Patrick banished the serpents of Ireland, he was really banishing the old religion from the sacred isle.

Jeff Fitzpatrick’s work is a journey. It is a journey of the spirit, through time and understanding, a quest for the mystic center.

The work is a mental journey as well. The incredible intricacies of the interlace are a studied design and problem solving effort. It is a quest for beauty of color, form, content and balance.

At the time of this writing, Jeff is quite literally on a journey looking for an audience for his art. In Ireland he laments that he is not taken seriously by the establishment of galleries and museums. "I was never encouraged in school to pursue Celtic art because it was not seen as important. Celtic art is seen as commercial art" he will explain. "Our national art form is seen as something that has no place in the present, other than as greeting cards or calendars and designs for crafts." Americans who have discovered Jeff’s work seemed more enthusiastic about it than the native Irish. Encouraged by this in May and June of this year he traveled to America and found an eager audience for his art among the Celtic Diaspora in the United States. Groundwork has been laid for several exhibitions in the next year.

Jeff is pioneering an appreciation for original works of Celtic art by only showing originals. Celtic art, unfortunately has been debased in its perceived value since so much of it has been reproduced for sale in relatively cheap formats. There are not yet galleries devoted to original works by Celtic artists or any well known collections in the genre of modern Celtic art. Original works that take weeks or even months to complete require a serious appreciation if they are to stand on their own, rather than sell in reproduced multiples.

Jeff has worked for years with modern graphics materials but is now experimenting on goat skin. His recent work with Claidhbh O’Gibne in woodcarving has resulted in some spectacular pieces. Now Jeff has expressed an interest in working in bronze. These choices of traditional materials would indicate that the work of Jeff Fitzpatrick is traveling back in time. His painstaking mastery of detail and his passionate quest for cultural and spiritual authenticity also seem like he might be looking backwards rather than forwards. Yet these same concerns for the material, mental and spiritual are what made Celtic art vibrant, exciting and original a millennia ago. It is an old formula, but one that applied faithfully creates what has never been seen before.

Stephen Walker

June 1999

Jeff is currently living in the west of Ireland. Visit his web site http://www.irishcelticilluminations.com/

Go to Walker Metalsmiths Shopping Site

Other articles by Stephen Walker published

in Dalriada Magazine

Celtic Interlace; An Overview Part 1

Celtic

Interlace; Continuum Part 2

Celtic

Interlace; Continuum Continued (part 3)

In Search of

Meaning (part 4)

Reading List Recommended Links and Books